"It was real," confirms Simon Weckert, his answer giving this interview about his Google Maps hack a reason to exist.

My question, if you missed the viral sensation earlier in the month, was to triple-check if Weckert's 99-smartphones-in-a-cart-creating-traffic-on-Google-Maps-in-Berlin art project, was real or not.

The tall, thin artist is wearing Berlin's uniform of black, his shirt emblazoned with a Netzpolitik logo in his studio in Kreuzberg, and he smiles and nods enthusiastically about his project and the elements behind simple, effective disruption.

Weckert's concept was to take a symbolic number of 99 different Android smartphones, 99 different Google accounts, 99 SIM cards (each providing for a unique connection), and drag them around streets in Berlin. The cart would travel even outside of Google's own offices, creating a temporary traffic jam; the whole thing shot and uploaded to YouTube as proof. The irony of using Google's own services and platforms to create the effort, and publicize it, was a key part of the concept.

To confirm the idea further, others have since re-created the Google Maps gridlock hack, in one case using as few as 20 phones to create a traffic jam.

How it came about: a year of planning

The idea came to Weckert three years ago, at a May Day (May 1) demonstration in Berlin.

"I saw a lot of people compressed, walking on the street. I had a look at Google Maps traffic and saw a super huge traffic jam in the area that I was in, despite literally not a single car nearby," explains Weckert.

"I thought it was interesting: would it be possible to reproduce or generate such a traffic jam by myself. I thought: I don't need the people, I just need the smartphones."

A year of planning, 99 phones borrowed and rented, all for a single day of hacking Google Maps

It took Weckert more than a year of planning to get enough devices gathered together for a single day. No manufacturer or retail outlet selling phones was willing to participate, and buying enough even second-hand wasn't feasible for a project without funding.

In the end, he managed to convince enough friends and connections to borrow their phones for a single day, including their Google accounts and SIMs, and hired other smartphones for the day from rental services that supply businesses and conferences for use and testing. All phones were charged in advanced.

A plan in motion

Once assembled and checked, each phone was put into navigation mode — something that Weckert admits may have been unnecessary given Android's sharing of data to Google, but no chances were being taken despite the extra effort required.

No tests or dry-runs were taken in advance, with Weckert and a small group preparing and executing the performance, including the red cart — chosen purposefully for the squeaking wheel and bright red color. Weckert described it as adding a "childhood, playful, super-analog" element to the dual narratives of the hack.

"That's what people really liked about it — one guy, 99 smartphones, interrupting the system.

"But there are two layers to the project. One is the technical element, the other is the easy-to-understand 'Robin Hood' effect with the cart, where one identity is in contrast to a huge tech giant, trying to put a little impact into the engine behind it. It's easy to understand, and reached a broad audience," explained Weckert.

Small, simple hacks can break down, complex systems

"But it has a wider meaning: small, simple hacks can break down, complex systems. A Chaos Computer Club project presented last year at 36C3 showed how a complex and 'secure' healthcare system data scheme could be easily hacked by people pretending to be doctors; a super simple solution to unlocking people's data.

"Developers care more about encryption and PGP or SHA-1 and elements like that, which of course are important, but often the technical side can be defeated by something far simpler."

Google hasn't been in touch with Weckert directly. In reply to queries at the time, Google offered a playful response: "Whether via car or cart or camel, we love seeing creative uses of Google Maps as it helps us make maps work better over time." But Weckert hasn't taken any chances and has been careful to not reveal the date the hack took place. This was to try to obfuscate any data Google might be sieving, in order to avoid any kind of retaliation on the Google accounts that were used on each phone.

Google Maps and disputed regions

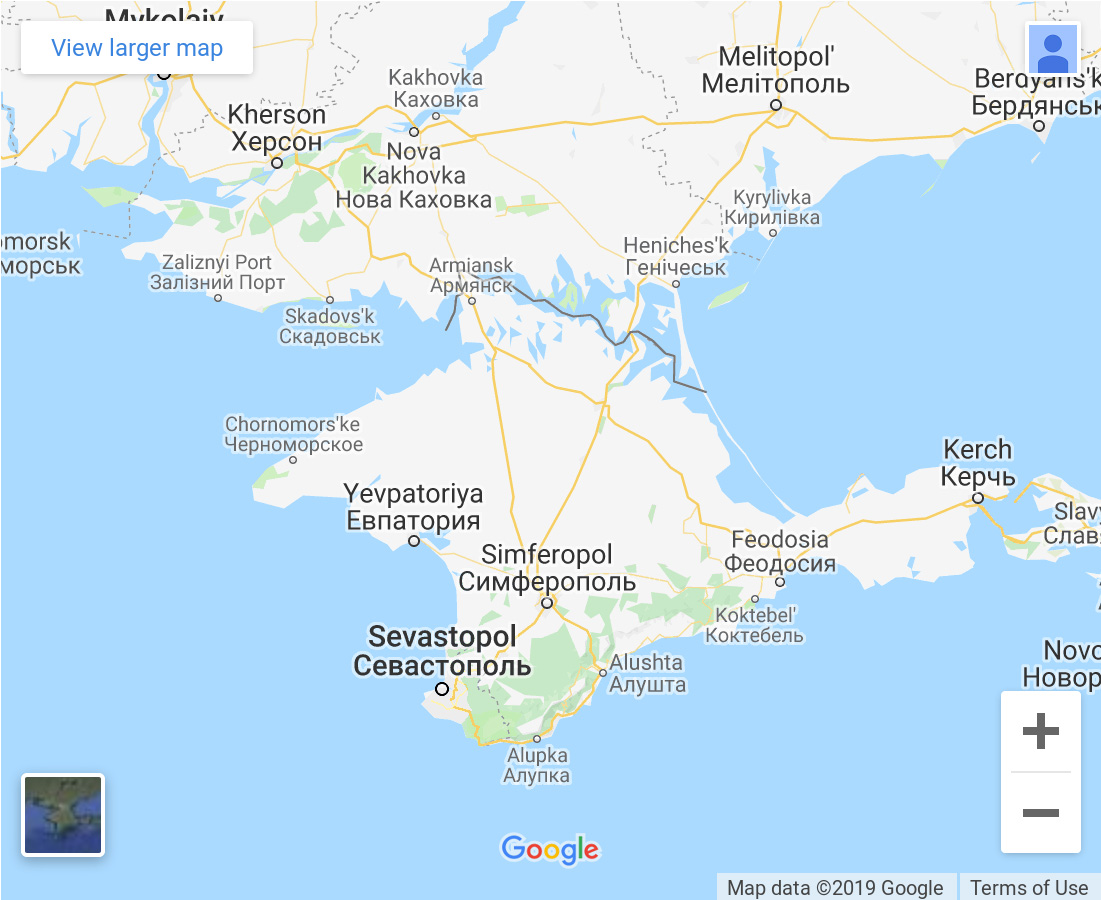

Weckert said he has seen another of his Google Maps projects stop working due to a (possibly unrelated) change to a Google API. That project, called Google Maps Borders, was one of the first to show considerable detail of how national boundaries are represented differently by some countries, depending on which "Google" entity you are using – e.g. Google in India, or Google in China, as compared with Google in the US.

Here's two regions compared between neighboring Google Maps versions: China and India, and Ukraine and Russia, originally found by Weckert:

Google Maps China Google Maps India

Google Maps China Google Maps India

Google Maps Ukraine Google Maps Russia

Google Maps Ukraine Google Maps Russia

This is freshly in the news again, after revelations that Google has "a special team employees refer to as 'the disputed region team' that addresses prickly matters, such as how to portray the Falkland Islands, whose ownership has been disputed between the United Kingdom and Argentina since the latter invaded in 1982 and claimed them (Google makes no mention of the Argentine name Islas Malvinas to English map surfers)," per the Washington Post this week.

Weckert isn't stopping his clever Google hacks, hinting at another Maps-focused project he's been working on for more than six months that will be taking place sometime soon in Berlin, again. If Google isn't onto him, already.

More posts about google

from Android Authority https://ift.tt/2HOCTVE

via IFTTT

Aucun commentaire:

Enregistrer un commentaire